This post highlights recent intellectual property cases and resources for further research on intellectual property law.

Read morePublic Domain Day 2023: IA, IP, and E-Books

Public Domain Day is the yearly celebration of a new group of copyrighted creative works entering the public domain, making them freely accessible to all. Public Domain Day is the perfect opportunity to learn about legal concepts and challenges surrounding intellectual property law and how this evolving area of law affects libraries. The pandemic has increased the demand for access to digital materials as large book publishers merged while library in-person services became limited, resulting in raised tensions between authors, publishers, and libraries.

Read morePlease Hold: The Origins of a Hated but Entirely Necessary Invention

“Telephone hold program system” | US. Patent No. US3246082A | Alfred Levy (Granted 1966)

Last Thursday, NPR published a story about a deceptively dull topic — hold music. The history of this much maligned loop of sound that’s designed to pacify impatient callers is more compelling than one might expect. Along with an interesting origin story about the history of hold music, the NPR essay explored the psychology of selecting the most appropriate music for a particular purpose. A funeral home or debt collector will play music that soothes, while a car dealership may offer something more upbeat, overlaid with branded messages or “sincere thanks” for your patience. No matter the secondary purpose of the selected songs, most everyone agrees that hold music should be innocuous and inoffensive, and it should communicate one essential thing — Don’t hang up! Someone will be with you soon.

What does any of this have to do with the law, you ask? Well, your question is important to us. For starters, there’s the invention of hold music itself, and while its origin is less momentous than the discovery of penicillin, this "music" came about in a similarly accidental way. Legend has it that a factory worker named Alfred Levy was inspired to file a patent application in 1962 for the “Telephone hold program system” when a wire came into contact with a steel girder at the factory where he worked, turning the factory into a giant radio. Music, transmitted through the wire to the steel beam, could be heard through the phone lines that, until then, had been silent. Some years later, Levy filed a second patent application for a “Remotely controlled telephone hold program system" that gave callers the freedom to decide which music they wished to hear, lest the same song on continuous repeat should grow tiresome. Clearly, Levy was an innovative sort who was also concerned with courteous telephone practice.

Levy's invention is now so commonplace that the absence of any sound on the end of the line is disconcerting. According to the NPR story, even on non-hold calls, companies transmit a “comfort tone” over phone lines, a “barely audible synthetic noise that signals a connection is still there.” No one likes to feel forgotten or lost in a void of silence (except perhaps one man who “loves being in that uncertain and boring middle most of us dread — on hold, listening to hold music”), so providing reassurance that someone is listening (or at least present) on the end of a phone line has become a routine practice.

Alfred Levy understood that the goal of any effective hold music is to distract, to draw attention away from the tedium and duration of holding the line. While it may accomplish little to simply acknowledge an on-hold caller’s frustration, actually calling attention to the purpose of hold music is, as it turns out, a secret of success for at least for one company.

UberConference, a web conferencing service from Dialpad Communications, has garnered a lot of attention for its creative use of hold music to entertain its customers. Instead of hearing the usual Muzak-style arrangements or tinny corporate selections that we all know so well, UberConference users are treated to a song called, “I’m On Hold” by UberConference co-founder and amateur singer-songwriter Alex Cornell. The song, a pleasant, county/folk melody designed specifically for the phone, is simple and catchy with a single guitar and vocals. It's the perfect recipe for a song that’s played over an analog phone line where music is necessarily compressed, and sound quality suffers. Since 2013 when the song debuted, it has generated serious social media buzz. Callers appreciate the song’s references to being on hold, waiting for other callers to join the conference, and the uncertainty of knowing if the call will ever begin. As writer and performer of this clever tune, Cornell holds copyright. Others may wish to use the song as their hold music, but allocating that right is Cornell’s alone. In the 1980s when companies simply pumped in music from the radio, copyright was not considered (or it was knowingly violated) even though, according to an article on Tedium.com, ASCAP designates hold music as a “public performance” that requires proper copyright clearance. Now, while hold music has its moment in the sun, conference callers everywhere can enjoy a little departure from the everyday Clare de Lune or the fleetingly popular Cisco hold music. Conference callers, including lawyers and librarians, can be entertained and amused while enjoying a properly cleared, copyrighted, piece of music designed for just the occasion.

Bad Blood: Taylor Swift and Artists’ Rights to Sound Recordings

Taylor Swift in 2019.

Earlier this week, Nashville-based record label Big Machine Label Group was purchased by music industry heavyweight Scooter Braun for a reported $300 million. This acquisition includes the master tapes for all of pop megastar Taylor Swift’s six albums released to date. The Swifties, dedicated members of the musician’s loyal international fandom, have taken this particularly hard, as Braun and Swift have been at odds over the years, leading to widespread suspicion that the purchase of the masters may have been motivated in part by personal animus.

What does this purchase mean for Swift, and does she have recourse?

The term master recordings refers to the ultimate, highest quality record of an artist’s studio session. It is the base from which all production and mixing occurs to bring a final version to the masses. “Sound recordings are inevitably derivative works as they necessarily include an audible performance of a literary, musical, or dramatic work.” §8:42 Publication of Works Other Than Sound Recordings, 1 The Law of Copyright. The right to create a derivative work is part of the so-called Bundle of Rights afforded a copyright holder, and therefore in theory the exclusive right to create a derivative work belongs to the author of the underlying work. However, authors can sell or assign rights from their bundle to others, and in the music business it is common for artists to sign their rights to master recordings over to their record labels. This was the case for Swift, who signed her deal with Big Machine Label Group at age 15. Still, because Swift retains the copyright in the underlying work, Braun would be unable, for example, to license the recordings for use in a film without Swift’s permission. These limitations on Braun’s ability to exploit the masters for monetary gain may be of some comfort to Swifties everywhere.

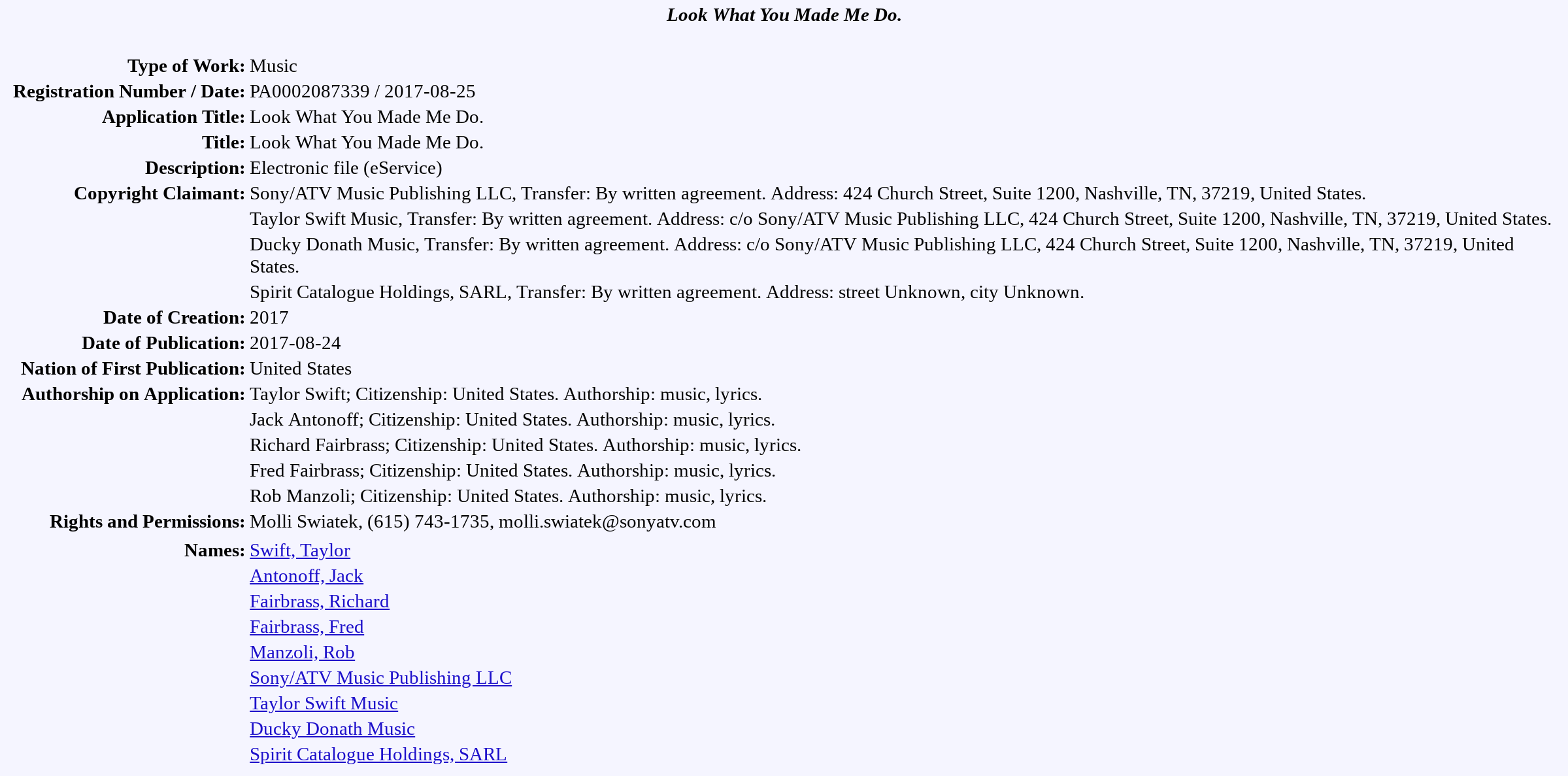

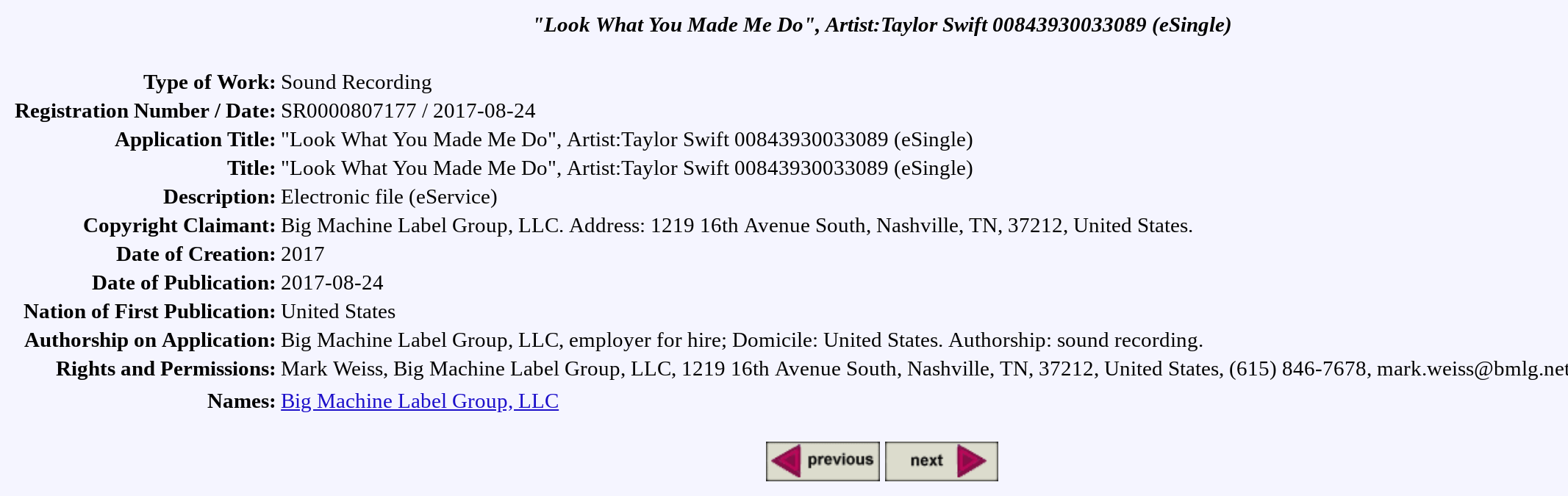

In the two image captures immediately below from the US Copyright Office online registration database, you can see that while Swift and others own the rights to the underlying musical work “Look What You Made Me Do,” Big Machine Label Group LLC owns the right to the “Look What You Made Me Do” sound recording.

Because her contract, as is typical of record deals, apparently did not include any right to first refusal on a deal for her master recordings, nor does it appear to have required the label to allow her to match any offer, analysis by The Hollywood Reporter indicates she has no legal recourse.

Yet, Taylor Swift has to date been about as significant a force on the business side of the music industry as she has been as an artist. It is likely that a result of this highly publicized incident will be a rise in contractual language providing artists with enhanced ability to eventually purchase back their own masters from their labels. As artists have struggled for decades to find ways to regain control of their tapes, this could well prove a pivotal moment in Entertainment Law.

Besides legal rights and the ability to commercially exploit master recordings, the owner of such recordings also must tackle issues of preservation. The recent, shocking New York Times Magazine expose of the almost 200,000 master tapes lost in the 2008 Universal Studios fire explores the repercussions of leaving cultural patrimony in the hands of for-profit institutions that may not be able to ensure preservation.

Intellectual Property and the NFL

In 2017, NRG Stadium in Houston hosted more than 70,000 football fans for Super Bowl LI. To do our part in supporting the event, we considered the legality of creating and sharing GIFs that feature NFL footage. In recognition of this year’s big game, Super Bowl LIII, which kicks off in Atlanta at 5:30 pm (CST) on Sunday, February 3, we are revisiting the topic of using NFL clips to create and share GIFs on social media. Many fans will capture game video with the hopes of turning a fantastic play or a memorable touchdown celebration into a GIF for all the world to see on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr. For its part, the NFL strongly discourages the use of its images, so for those of you hoping to create the next viral meme, let the law be your guide.

The NFL is notoriously protective of its brand. All text, images, photographs, video, audio, and graphics are tightly controlled, and any use of the NFL's content must comply with the NFL.com Terms and Conditions Agreement. Nonetheless, ripping images or video from television broadcasts is a popular way to create the GIFs and other graphic memes that fill our news feeds, and football replays are some of the most widely shared.

When news outlets use GIFs to enhance a story, they often rely on the fair use defense, but legal experts question the plausibility of such claims. Ricardo Bilton, Staff Writer at Digiday.com, describes the legal murkiness of sports highlight GIFs, saying that fair use may not apply. When publishers rip video highlights and repost them unaltered online, those content providers reap the benefits of increased ad revenue. However, as the popular websites, Deadspin and SB Nation, found out, fair use has its limits, and legislation such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act can be invoked to support claims of copyright infringement.

Those who appropriate content without paying the rebroadcasting fees that sports leagues, including the NFL, typically require must be careful. As long as the new content is "derivative of the original and does not create economic competition for copyright holders," the NFL will evaluate it on a case-by-case basis.

As for the armchair quarterback and amateur image manipulator, the same rules apply. Remixing and repurposing content to parody or critique your favorite plays of the game seems to follow the spirit of fair use. Unless the NFL sends you a takedown notice, your GIF of the game-winning catch, modified for new utility and meaning with no intent to profit, is probably safe.

But what about using the official name of the Big Game to advertise an event, for example? The Electronic Frontier Foundation has considered this very question, saying that, in their estimation, the terms “Super Bowl” and “Super Sunday” can be used to promote game day parties. Specifically, they mention the “nominative fair use” of trademarks:

“Having a trademark means being able to make sure no one can slap the name of your product onto theirs and confuse buyers into thinking they’re getting the real thing. It also means stopping an instance where using the name might make someone think it’s an endorsement or sponsorship. If neither of those things happens, you can call the Super Bowl the Super Bowl. The ability to use something’s trademarked name to identify it—even in a commercial—is called “nominative fair use.” Because the trademark is its name.”

The takeaways, according to those who have explored this topic (See links throughout this blog post.), are the following: Calling your Super Sunday celebration what it really is – a Super Bowl Party, not just a Big Game Party -- is probably okay. And hitting record on your DVR to capture all the best plays for your own fair use GIF is likely to be okay as well. May your Super Bowl Party be a day to remember, may the best GIFs go viral, and may the best team win!