Taylor Swift in 2019.

Earlier this week, Nashville-based record label Big Machine Label Group was purchased by music industry heavyweight Scooter Braun for a reported $300 million. This acquisition includes the master tapes for all of pop megastar Taylor Swift’s six albums released to date. The Swifties, dedicated members of the musician’s loyal international fandom, have taken this particularly hard, as Braun and Swift have been at odds over the years, leading to widespread suspicion that the purchase of the masters may have been motivated in part by personal animus.

What does this purchase mean for Swift, and does she have recourse?

The term master recordings refers to the ultimate, highest quality record of an artist’s studio session. It is the base from which all production and mixing occurs to bring a final version to the masses. “Sound recordings are inevitably derivative works as they necessarily include an audible performance of a literary, musical, or dramatic work.” §8:42 Publication of Works Other Than Sound Recordings, 1 The Law of Copyright. The right to create a derivative work is part of the so-called Bundle of Rights afforded a copyright holder, and therefore in theory the exclusive right to create a derivative work belongs to the author of the underlying work. However, authors can sell or assign rights from their bundle to others, and in the music business it is common for artists to sign their rights to master recordings over to their record labels. This was the case for Swift, who signed her deal with Big Machine Label Group at age 15. Still, because Swift retains the copyright in the underlying work, Braun would be unable, for example, to license the recordings for use in a film without Swift’s permission. These limitations on Braun’s ability to exploit the masters for monetary gain may be of some comfort to Swifties everywhere.

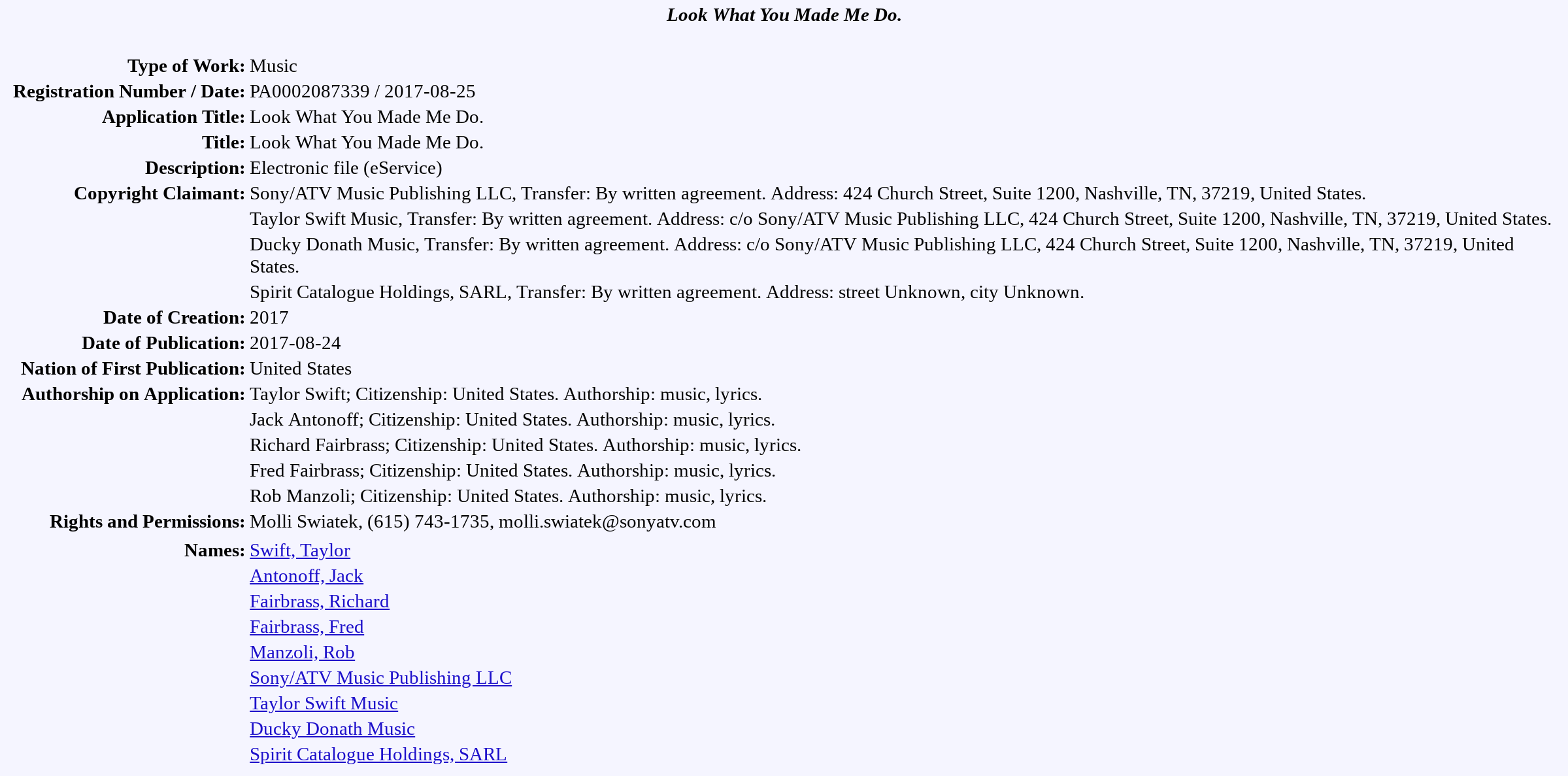

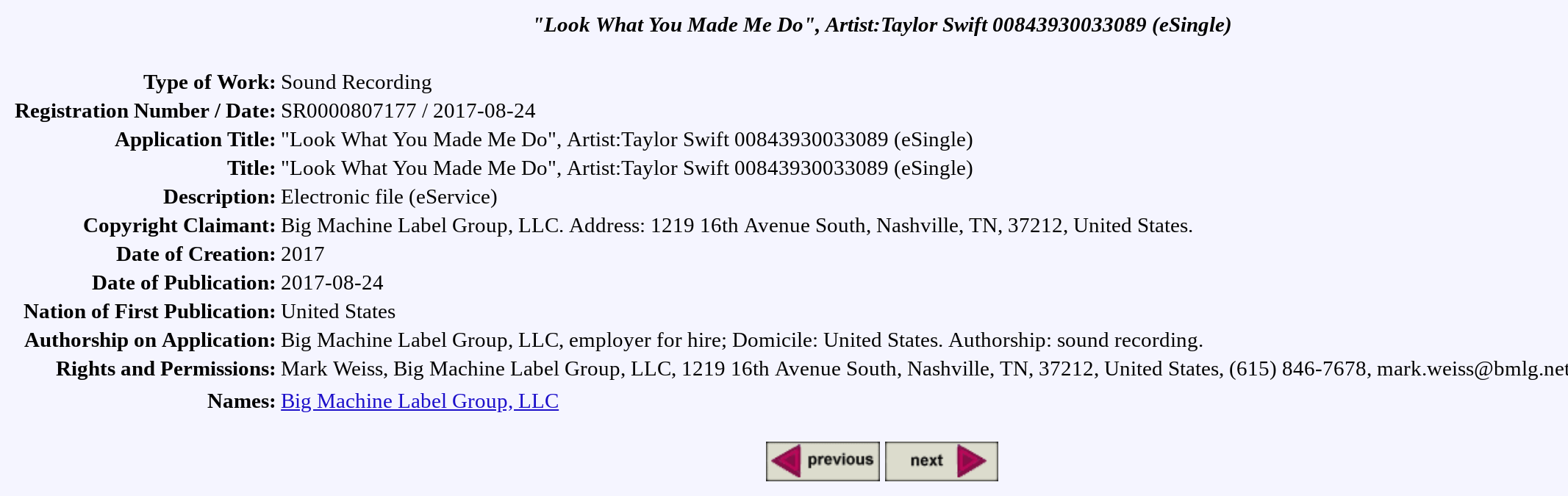

In the two image captures immediately below from the US Copyright Office online registration database, you can see that while Swift and others own the rights to the underlying musical work “Look What You Made Me Do,” Big Machine Label Group LLC owns the right to the “Look What You Made Me Do” sound recording.

Because her contract, as is typical of record deals, apparently did not include any right to first refusal on a deal for her master recordings, nor does it appear to have required the label to allow her to match any offer, analysis by The Hollywood Reporter indicates she has no legal recourse.

Yet, Taylor Swift has to date been about as significant a force on the business side of the music industry as she has been as an artist. It is likely that a result of this highly publicized incident will be a rise in contractual language providing artists with enhanced ability to eventually purchase back their own masters from their labels. As artists have struggled for decades to find ways to regain control of their tapes, this could well prove a pivotal moment in Entertainment Law.

Besides legal rights and the ability to commercially exploit master recordings, the owner of such recordings also must tackle issues of preservation. The recent, shocking New York Times Magazine expose of the almost 200,000 master tapes lost in the 2008 Universal Studios fire explores the repercussions of leaving cultural patrimony in the hands of for-profit institutions that may not be able to ensure preservation.