Harris County Law Library is hosting a symposium in honor of the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment and the progress made by the women’s suffrage movement. Registration is now open for this important program, which be held on Tuesday, August 18, 2020, from 2 p.m.-4 p.m., via GoToWebinar. Attendees can receive 2.0 hours CLE, including 1.0 hours ethics in Texas, provided by the Harris County Attorney’s Office.

Law Library Director Mariann Sears, the first woman to serve as Director of the Law Library, will open the symposium by welcoming three notable women in the legal profession to discuss the history of voting rights for women and the importance of inclusion in law and government. The speakers include: Marie Jamison, a partner at Wright, Close & Barger, who will share her research into the history of the 19th Amendment and the progress that followed; Renee Knake Jefferson, a professor at University of Houston Law Center, who will discuss the research for her book, Shortlisted: Women in the Shadows of the Supreme Court, and Justice Frances Bourliot, a judge for the Texas 14th Court of Appeals, who will discuss the importance of inclusion on the bench and share her experience as an appellate justice.

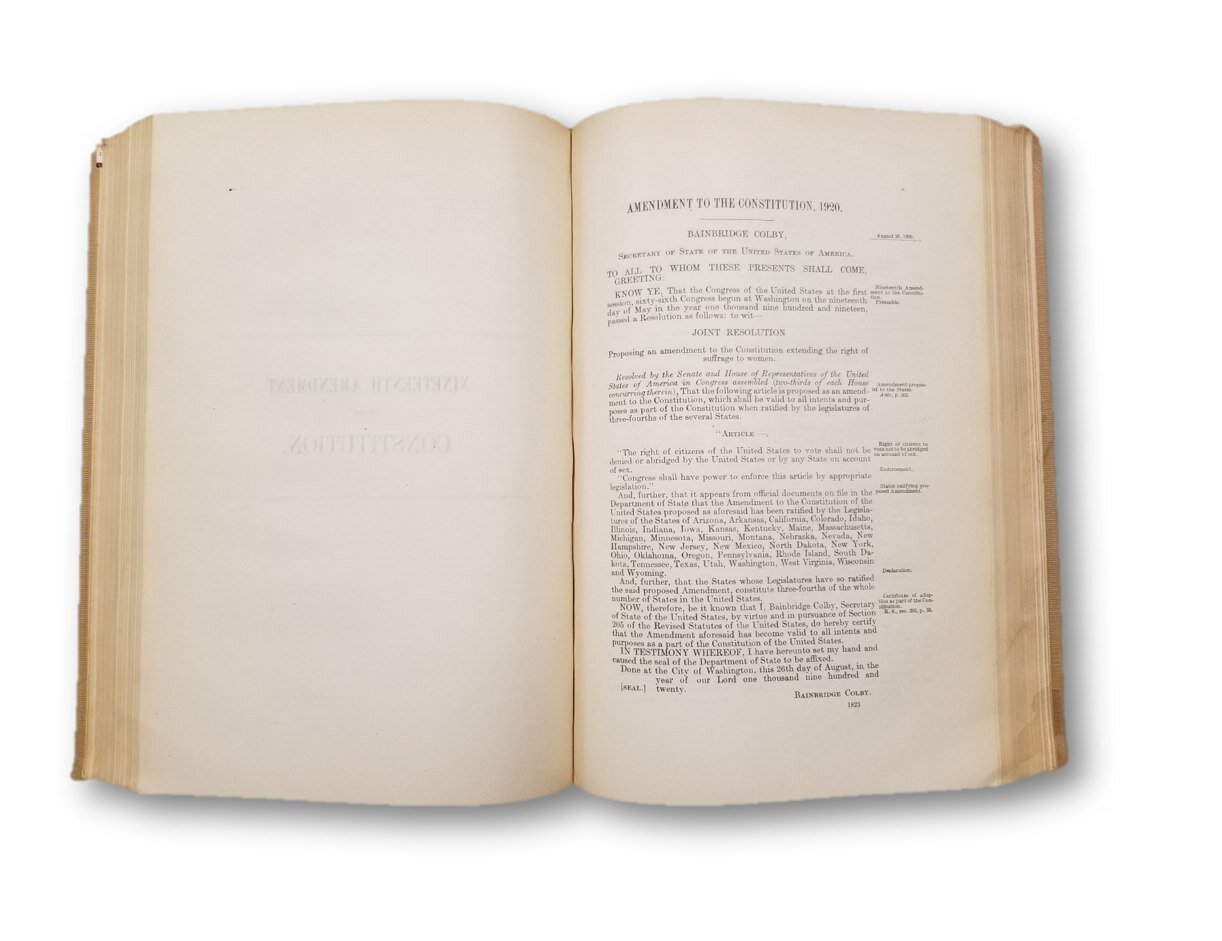

The date selected for the symposium is the 100th anniversary of ratification of the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920. On that day, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, which Congress passed on June 4, 1919, and Texas ratified on June 28, 1919. To learn more about the path of the 19th Amendment toward ratification and the history of the brave suffragists, like Jovita Idar, who pressed for the right to vote in Texas, visit the exhibit “Texas and the 19th Amendment” from the National Parks Service.