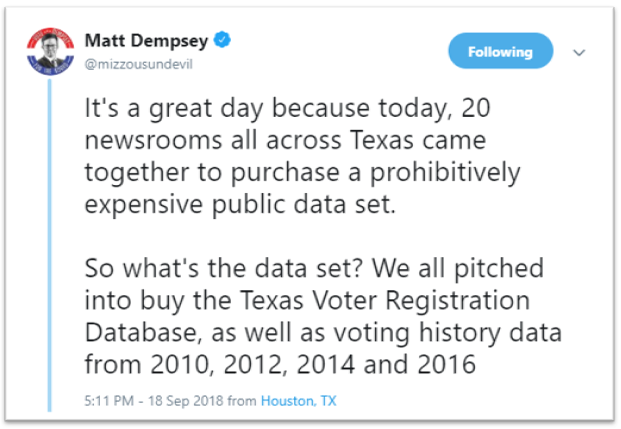

In a Twitter post on Wednesday evening, Houston Chronicle data editor Matt Dempsey announced the acquisition of Texas voter registration data, which was purchased collaboratively by 20 newsrooms across Texas. Calling themselves the Texas Open Data Consortium, these news outlets will use the newly acquired information to report on voter demographics, the upcoming midterm elections, the geographic concentration (by ZIP code and/or county) of newly registered voters, the number and common characteristics of voters removed from the rolls, and much more. As a data analyst, Matt Dempsey was justifiably excited about the acquisition of this database, as were those who champion open data and free access to information. “This is a fantastic thing for open data, for journalism in Texas, for better and more in-depth stories on our electorate across the state,” Mr. Dempsey tweeted.

On Twitter, news of this collaborative effort was mostly well-received, but two questions emerged again and again: (1) Why isn’t this data already publicly available? and (2) How much did the database cost? Mr. Dempsey answered repeatedly that the Texas Voter Registration Database is not subject to a Public Information Act request and can only be obtained from the Texas Secretary of State as governed by Chapter 18 of the Texas Texas Election Code. Indeed, the law states specifically how copies of the dataset must be furnished upon request (§18.008) and what fees the registrar may charge for fulfilling such requests (§18.010). Each of the 20 news outlets who participated in the purchase contributed $180 for a total cost of roughly $3,600, according to Mr. Dempsey’s Twitter responses. (To purchase your very own Texas Voter Registration Database, click here.)

Each of the newsrooms provided a signed affidavit stating that the data would not be used for commercial purposes. All participants also agreed not to publish the data online, citing “a lot of concern among the public about this data set” and the need to exercise caution by protecting voters’ privacy. The Election Code (§18.009) clearly prohibits using the information “in connection with advertising or promoting commercial products or services.” The data will be used for news gathering only. Twitter responders from other states (Pennsylvania, New York, Washington) were incredulous that Texas exacts such a steep price for furnishing voter data, and others expressed their suspicions about how this data will actually be used, but for those who advocate for open data initiatives and responsible journalism, this is one for the win column.