Observing the 50th Anniversary of Miranda v. Arizona

Law Day 2016

While the words contained in a Miranda warning may be familiar, this year's Law Day theme encourages all Americans to consider how those words have come to symbolize the procedural safeguards that protect our constitutional rights as we mark the 50th anniversary of the historic decision from which they arise. Explore the exhibit below to learn more about Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), the history that led to the landmark case, and its subsequent impact on American society.

The Road to Miranda V. Arizona

Although many reacted to the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Miranda v. Arizona as one that imposed new requirements on law enforcement and the criminal justice system, the Court discussed the ancient roots of the privilege against self-incrimination. Certainly, the road to Miranda v. Arizona can be traced back to the founding of the United States with the passage of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. For much of the following two centuries, the U.S. Supreme Court issued opinions concerning the rights afforded those accused of crimes under the Fifth Amendment's self-incrimination clause. Each of the rights addressed in the warnings required by the Court's landmark 1966 decision stem from a previous decision that paved the Road to Miranda v. Arizona.

You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

Perhaps the most iconic of statements that comprise the Miranda warnings is "you have the right to remain silent." Although this statement is most closely associated in the American psyche with Miranda v. Arizona, the Court, in its opinion, cited to the late 19th century case Bram v. U.S., 168 U.S. 532 (1897), to show that the Fifth Amendment prohibited the coercion of involuntary confessions. The thrust of the Court's mandate in Miranda v. Arizona was that law enforcement officers were required to inform suspects in custody of this long-standing right prior to initiating an interrogation.

You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you.

Although a right to counsel is guaranteed during criminal prosecutions by the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the right to counsel during an interrogation is discussed in Miranda v. Arizona as a means to protect Fifth Amendment rights against coercion. To make clear that all individuals were afforded such a privilege, the Court cited its three-year-old opinion Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), in which the Court articulated that poor defendants have the right to appointed counsel in criminal cases.

Who was Ernesto Miranda?

At the time of his arrest, Ernesto Miranda was a poor, 23-year-old man with a 9th-grade education who was accused of kidnapping and rape. During his interrogation, he was kept in isolation and never informed of his Fifth Amendment rights. At first, he maintained his innocence, but after two hours in the interrogation room, he signed a confession. The confession was used at trial and Miranda received a sentence of 20 to 30 years in prison.

Miranda v. Arizona in the U.S. Supreme Court

Reported as Miranda v. Arizona, 382 U.S. 436 (1966), the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decision was handed down on June 13, 1966. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the Court’s opinion. In overturning the convictions of Miranda and three other defendants in consolidated cases, the Court made clear that police had a constitutional duty to prevent coercion in interrogations by informing individuals in custody of their Fifth Amendment rights. To fulfill that duty, officers are required to inform suspects of their rights to remain silent and to speak with an attorney prior to questioning.

Miranda V. Arizona in Pop Culture

Miranda on the small screen

In a 2011 law review article, Professor Ronald Steiner described the swiftness with which Miranda warnings were integrated into pop culture. Within a year after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion, Sergeant Joe Friday - played by Jack Webb {photo here} - read Miranda warnings to place suspects under arrest in the popular police drama Dragnet.

Miranda in real life

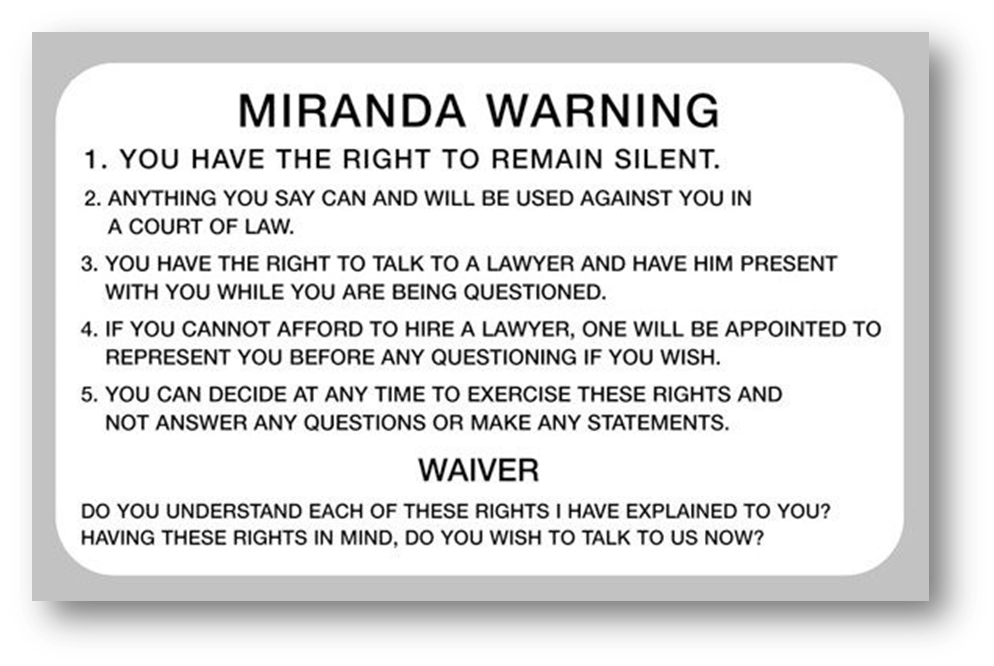

While Joe Friday was issuing Miranda warnings from memory on the small screen, real law enforcement officers were issued cards to read suspects their rights prior to interrogations.

To see real cards used by officers in Harris County, Texas, visit the Law Library throughout the month of May to view the Law Day 2016 exhibit at our downtown location.

Law Day, May 1, 2016 - Miranda: More Than Words

Law Day is the annual celebration of the rule of law designated by Congress to occur each May 1st. This year's theme, established by the American Bar Association's National Law Day Committee, encourages all Americans to observe the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miranda v. Arizona by considering the procedural protections that safeguard our constitutional rights. At the Harris County Law Library, we will celebrate Law Day with an exhibit featuring the landmark case as well as the cases that form the basis of the rights discussed in Miranda and its impact on American life.

Visit www.lawday.org for more information on Law Day and related observances.